Visualizing the Volta potential in DFT calculations

Let's talk about the Volta potential. Users of quantum mechanical simulations such as density functional theory - including myself - often overlook "classical" thinking of the electrostatic field. In most of the finite-sized or continuous boundary calculations, the local electric field (defined as the negative gradient of electric potential) does not mean much. The electric potential changes rapidly near ions and electrons densities, and the total field averages to zero. But that may not be true if your system is asymmetrically charged. And having two different conductors in your system can easily make your system asymmetrically charged.

Volta potential is essentially the same potential difference as the Galvani potential between two conductors but separated by a distance. It is the potential difference driven by the alignment of the Fermi level of two conductors with different work functions when they are brought into electrical contact.

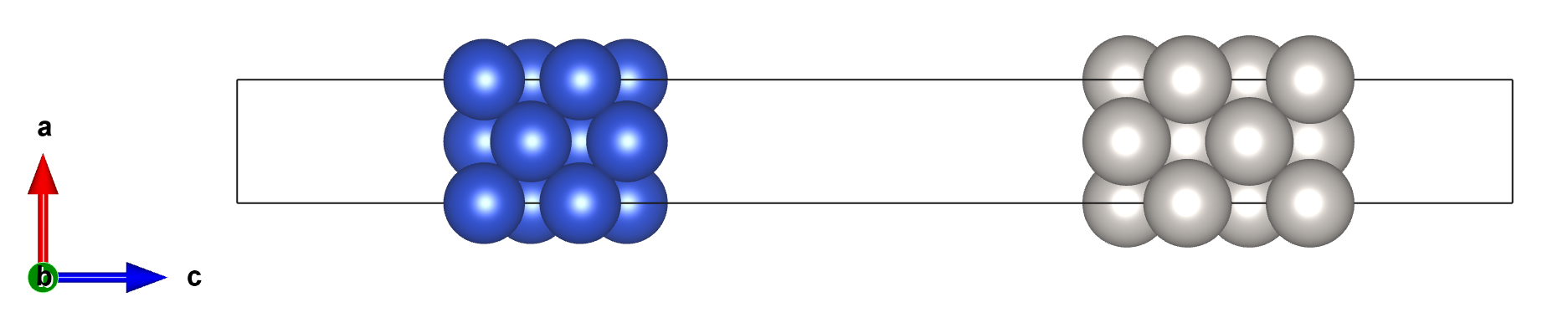

Consider a system of two separated slabs of different metals, 4-layer Cu(100) (represented as blue spheres) and Pt(100) (represented as gray spheres). With slight biaxial strain in both slabs, the calculated workfunctions are 4.41 and 5.77 eV respectively. While they look perfectly separated, the Volta potential forms between the electrodes and there is charge transfer from the Cu slab (with a lower work function) to the Pt slab (with a higher work function). That is because in DFT calculations, electrons in the whole unit cell occupy states represented by wave functions, also of the whole unit cell. The states are occupied starting with the ones with the lowest eigenvalue, regardless of from which ion they originate. Since only one Fermi level can be assigned for the unit cell, all the conductors in single DFT calculations can be thought of as electrically connected by an external wire.

Volta potential is not an artifact of DFT calculations, it is a real effect. If two infinitely large metal slabs (electrodes) with different work functions were connected by external wire, a uniform electric field would form between the electrodes. If it's real - does it mean that it's not problematic? Unfortunately not. What makes the Volta potential problematic is the scale of the DFT calculations. In experiments, the parallel plate electrodes are often separated by over ~100 nm. In this length scale, the magnitude of the electric field formed by the Volta potential would not be too significant. However, it is not easy to simulate electrodes separated by over 100 nm in DFT calculations, let alone 100 Å. The length between the electrodes is simplified and shortened dramatically, so the magnitude of the electric field formed by the Volta potential increases dramatically. In this system, the magnitude of the electric field is about 0.12 V/Å, or 1.2 MV/mm.

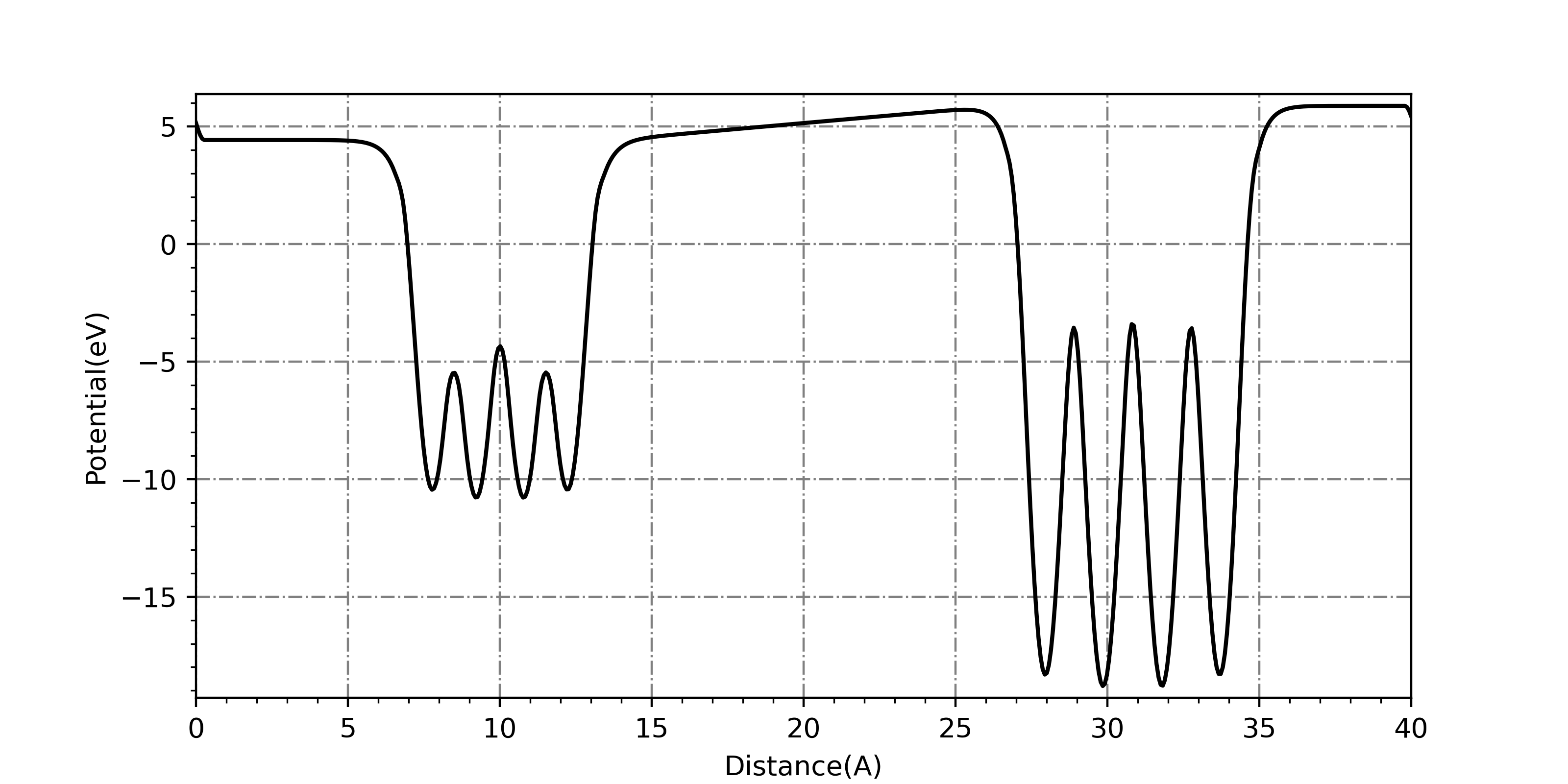

The easiest way to visualize the Volta potential is by using pre-existing codes to plot plane-averaged potentials. There are several post-processing packages that can do this, such as p4vasp or ASE. I used a script from @Ionizing as a base to plot the plane-averaged potential of the Cu-Pt system. Note that the values of the y-axis are not the electric potential, but the potential energy of an electron - the sign is opposite.

The potential difference and the electric field in the inner vacuum between the slabs are clearly visible. In the outer vacuum, the dipole correction is applied to circumvent the continuous boundary conditions.

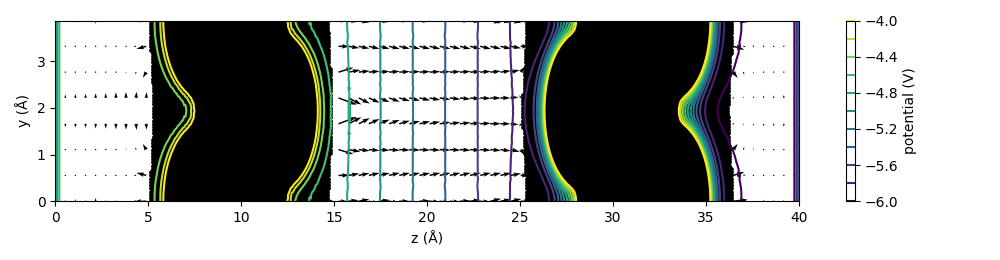

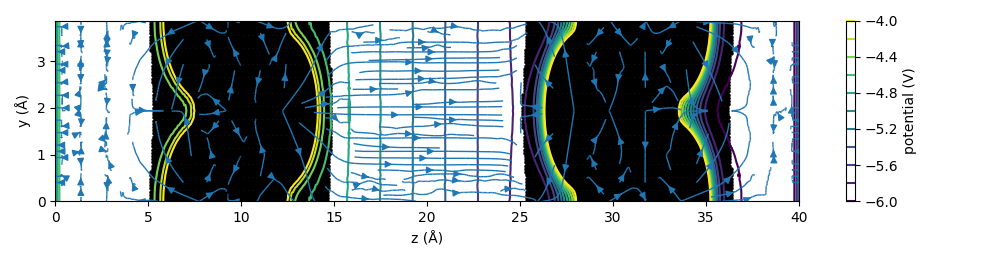

Taking it one step further, is it possible to visualize the electric fields in real space, using matplotlib functions such as quiver or streamline? It didn't result in the prettiest image, but here are my efforts.

First, you have to be able to read data files LOCPOT and CHGCAR. The files contain raw data of electronic potential energy and charge density as a 1D array, with 5 data points in each row. The grid points are those of the fine FFT grid of the system (NGXF, NGYF and NGZF). A simple script can be written to read this data and convert this array to a 3D array to handle the data better. One important thing to notice is to use the Fortran-like index ordering when reshaping the array.

#potential matrix

potential = np.zeros(grid[0]*grid[1]*grid[2])

#fill potential matrix

for i in range(int(grid[0]*grid[1]*grid[2]/5)):

line = locpot.readline()

potential[5*i:5*i+5] = np.array(line.split(), dtype=float)

#last line

if grid[0]*grid[1]*grid[2]%5 != 0:

line = locpot.readline()

potential[-1-len(line.split()):-1] = np.array(line.split(), dtype=float)

#reshape potential matrix

potential = np.reshape(potential, (grid[0], grid[1], grid[2]), order='F')

locpot.close()

With the 3D array of potential/charge density data in hand, the 3D data can be sliced and plotted in 2D. It is preferable to slice a mirror plane of the unit cell, where the out-of-plane components of the field should be zero. The field can be obtained as the negative gradient of the electric potential. However, for quiver plots, the micro potential gradient from the presence of particles far outweighs the field that is formed from the Volta potential in terms of magnitude. To visualize the macroscopic field, the microscopic fields have to be erased. I tried masking the electric fields at where the charge density is high, and where there is dipole correction.

grad = np.gradient(potential_fill, x_fig, y_fig, edge_order=2)

grad_X = -grad[0]

grad_Y = -grad[1]

#mask areas with high charges

grad_X[(charge_fill > 1)] = 0

grad_Y[(charge_fill > 1)] = 0

#mask areas at the dipole correction

if axis == 'x':

grad_X[(X.T < 0 + 0.3) | (X.T > c - 0.3)] = 0

grad_Y[(X.T < 0 + 0.3) | (X.T > c - 0.3)] = 0

elif axis == 'y':

grad_X[(Y.T < 0 + 0.3) | (Y.T > c - 0.3)] = 0

grad_Y[(Y.T < 0 + 0.3) | (Y.T > c - 0.3)] = 0

The resulting images correctly capture the idea of the Volta potential, but are not as smooth as expected. There seems to be a bit of a tradeoff in the visualization of potential contours and the field arrows/lines with respect to how many grid points are involved.

Finally, if you're still not convinced, let's count the charges themselves. The charge transferred should be countable just from the charge densities, as the charges are well separated. But to obtain more details, I used Bader charge analysis. The amount of charge should be \( A \epsilon_0 \mathcal{E} \), where \(A\) is the cross-sectional area, \(\epsilon_0\) is the vacuum permittivity, and \( \mathcal{E} \) is the electric field (Interestingly, the amount of charge transferred to match the Fermi level depends on the distance between the materials). The field strength is about 0.12 V/Å, and the cross-sectional area is 14.8 Å\(^2\) per unit cell. From these numbers, we expect 0.0098 electrons per unit cell to be transferred from Cu to Pt slab.

# X Y Z CHARGE MIN DIST ATOMIC VOL

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 0.000000 0.000000 7.750000 11.005522 1.188414 39.271973

2 1.938500 1.938500 7.750000 11.005522 1.188414 39.271973

3 0.000000 1.938500 9.215120 10.994546 1.179593 11.671614

4 1.938500 0.000000 9.215120 10.994546 1.179593 11.671614

5 0.000000 0.000000 10.762480 10.994377 1.179421 11.671662

6 1.938500 1.938500 10.762480 10.994377 1.179421 11.671662

7 0.000000 1.938500 12.227360 11.000732 1.188437 38.780684

8 1.938500 0.000000 12.227360 11.000732 1.188437 38.780684

9 0.000000 1.938500 27.900000 10.058692 1.336228 40.909388

10 1.938500 0.000000 27.900000 10.058692 1.336228 40.909388

11 0.000000 0.000000 29.806360 9.954864 1.317566 14.419555

12 1.938500 1.938500 29.806360 9.954864 1.317566 14.419555

13 0.000000 1.938500 31.743560 9.937026 1.328100 14.367011

14 1.938500 0.000000 31.743560 9.937026 1.328100 14.367011

15 0.000000 0.000000 33.649800 10.054118 1.338091 40.528537

16 1.938500 1.938500 33.649800 10.054118 1.338091 40.528537

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

VACUUM CHARGE: 0.0002

VACUUM VOLUME: 178.0043

NUMBER OF ELECTRONS: 168.0000

The Bader charges correspond to 0.010 electrons transferred from the Cu slab to the Pt slab. Also, the Bader charge analysis reveals that the Cu layer closest to the Pt slab lost ~0.005 electrons for each ion, and the Pt layer closest to the Cu slab gained ~0.005 electrons for each ion, which corresponds to the "classical" depiction of charge distribution of this system resulting from Volta potential.

The existance of the Volta potential calls for a careful analysis of electric fields in the system for DFT systems with two asymmetric electrodes, as it will tend to polarize inner material severely. It is one of the examples where limitations of calculations have to be considered regarding correspondance of DFT and experiments, like the band alignment at the metal-insulator interface.